WebGL2 GPGPU

GPGPU is “General Purpose” GPU and means using the GPU for something other than drawing pixels.

The basic realization to understanding GPGPU in WebGL is that a texture is not an image, it’s a 2D array of values. In the article on textures we covered reading from a texture. In the article on rendering to a texture we covered writing to a texture. So, if realizing a texture is a 2D array of values we can say that we have really described a way to read from and write to 2D arrays. Similarly a buffer is not just positions, normals, texture coordinates, and colors. That data could be anything. Velocities, masses, stock prices, etc. Creatively using that knowledge to do math, that is the essence of GPGPU in WebGL.

First let’s do it with textures

In JavaScript there is the Array.prototype.map function which given an array calls a function on each element

function multBy2(v) {

return v * 2;

}

const src = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

const dst = src.map(multBy2);

// dst is now [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12];

You can consider multBy2 a shader and map similar to calling gl.drawArrays or gl.drawElements.

Some differences.

Shaders don’t generate a new array, you have to provide one

We can simulate that by making our own map function

function multBy2(v) {

return v * 2;

}

+function mapSrcToDst(src, fn, dst) {

+ for (let i = 0; i < src.length; ++i) {

+ dst[i] = fn(src[i]);

+ }

+}

const src = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

-const dst = src.map(multBy2);

+const dst = new Array(6); // to simulate that in WebGL we have to allocate a texture

+mapSrcToDst(src, multBy2, dst);

// dst is now [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12];

Shaders don’t return a value they set an out variable

That’s pretty easy to simulate

+let outColor;

function multBy2(v) {

- return v * 2;

+ outColor = v * 2;

}

function mapSrcToDst(src, fn, dst) {

for (let i = 0; i < src.length; ++i) {

- dst[i] = fn(src[i]);

+ fn(src[i]);

+ dst[i] = outColor;

}

}

const src = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

const dst = new Array(6); // to simulate that in WebGL we have to allocate a texture

mapSrcToDst(src, multBy2, dst);

// dst is now [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12];

Shaders are destination based, not source based.

In other words, they loop over the destination and ask “what value should I put here”

let outColor;

function multBy2(src) {

- outColor = v * 2;

+ return function(i) {

+ outColor = src[i] * 2;

+ }

}

-function mapSrcToDst(src, fn, dst) {

- for (let i = 0; i < src.length; ++i) {

- fn(src[i]);

+function mapDst(dst, fn) {

+ for (let i = 0; i < dst.length; ++i) {

+ fn(i);

dst[i] = outColor;

}

}

const src = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

const dst = new Array(6); // to simulate that in WebGL we have to allocate a texture

mapDst(dst, multBy2(src));

// dst is now [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12];

In WebGL the index or ID of the pixel whose value you’re being asked to provide is called gl_FragCoord

let outColor;

+let gl_FragCoord;

function multBy2(src) {

- return function(i) {

- outColor = src[i] * 2;

+ return function() {

+ outColor = src[gl_FragCoord] * 2;

}

}

function mapDst(dst, fn) {

for (let i = 0; i < dst.length; ++i) {

- fn(i);

+ gl_FragCoord = i;

+ fn();

dst[i] = outColor;

}

}

const src = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

const dst = new Array(6); // to simulate that in WebGL we have to allocate a texture

mapDst(dst, multBy2(src));

// dst is now [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12];

In WebGL textures are 2D arrays.

Let’s assume our dst array represents a 3x2 texture

let outColor;

let gl_FragCoord;

function multBy2(src, across) {

return function() {

- outColor = src[gl_FragCoord] * 2;

+ outColor = src[gl_FragCoord.y * across + gl_FragCoord.x] * 2;

}

}

-function mapDst(dst, fn) {

- for (let i = 0; i < dst.length; ++i) {

- gl_FragCoord = i;

- fn();

- dst[i] = outColor;

- }

-}

function mapDst(dst, across, up, fn) {

for (let y = 0; y < up; ++y) {

for (let x = 0; x < across; ++x) {

gl_FragCoord = {x, y};

fn();

dst[y * across + x] = outColor;

}

}

}

const src = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

const dst = new Array(6); // to simulate that in WebGL we have to allocate a texture

mapDst(dst, 3, 2, multBy2(src, 3));

// dst is now [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12];

And we could keep going. I’m hoping the examples above helps you see that GPGPU in WebGL is pretty simple conceptually. Let’s actually do the above in WebGL.

To understand the following code you will, at a minimum, need to have read the article on fundamentals, probably the article on How It Works, the article on GLSL and the article on textures.

const vs = `#version 300 es

in vec4 position;

void main() {

gl_Position = position;

}

`;

const fs = `#version 300 es

precision highp float;

uniform sampler2D srcTex;

out vec4 outColor;

void main() {

ivec2 texelCoord = ivec2(gl_FragCoord.xy);

vec4 value = texelFetch(srcTex, texelCoord, 0); // 0 = mip level 0

outColor = value * 2.0;

}

`;

const dstWidth = 3;

const dstHeight = 2;

// make a 3x2 canvas for 6 results

const canvas = document.createElement('canvas');

canvas.width = dstWidth;

canvas.height = dstHeight;

const gl = canvas.getContext('webgl2');

const program = webglUtils.createProgramFromSources(gl, [vs, fs]);

const positionLoc = gl.getAttribLocation(program, 'position');

const srcTexLoc = gl.getUniformLocation(program, 'srcTex');

// setup a full canvas clip space quad

const buffer = gl.createBuffer();

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, buffer);

gl.bufferData(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, new Float32Array([

-1, -1,

1, -1,

-1, 1,

-1, 1,

1, -1,

1, 1,

]), gl.STATIC_DRAW);

// Create a vertex array object (attribute state)

const vao = gl.createVertexArray();

gl.bindVertexArray(vao);

// setup our attributes to tell WebGL how to pull

// the data from the buffer above to the position attribute

gl.enableVertexAttribArray(positionLoc);

gl.vertexAttribPointer(

positionLoc,

2, // size (num components)

gl.FLOAT, // type of data in buffer

false, // normalize

0, // stride (0 = auto)

0, // offset

);

// create our source texture

const srcWidth = 3;

const srcHeight = 2;

const tex = gl.createTexture();

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, tex);

gl.pixelStorei(gl.UNPACK_ALIGNMENT, 1); // see https://webglfundamentals.org/webgl/lessons/webgl-data-textures.html

gl.texImage2D(

gl.TEXTURE_2D,

0, // mip level

gl.R8, // internal format

srcWidth,

srcHeight,

0, // border

gl.RED, // format

gl.UNSIGNED_BYTE, // type

new Uint8Array([

1, 2, 3,

4, 5, 6,

]));

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_MIN_FILTER, gl.NEAREST);

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_MAG_FILTER, gl.NEAREST);

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_WRAP_S, gl.CLAMP_TO_EDGE);

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_WRAP_T, gl.CLAMP_TO_EDGE);

gl.useProgram(program);

gl.uniform1i(srcTexLoc, 0); // tell the shader the src texture is on texture unit 0

gl.drawArrays(gl.TRIANGLES, 0, 6); // draw 2 triangles (6 vertices)

// get the result

const results = new Uint8Array(dstWidth * dstHeight * 4);

gl.readPixels(0, 0, dstWidth, dstHeight, gl.RGBA, gl.UNSIGNED_BYTE, results);

// print the results

for (let i = 0; i < dstWidth * dstHeight; ++i) {

log(results[i * 4]);

}

and here it is running

Some notes about the code above.

-

We draw a clip space -1 to +1 quad.

We create vertices for a -1 to +1 quad from 2 triangles. This means, assuming the viewport is set correctly, we’ll draw all the pixels in the destination. In other words we’ll ask our shader to generate a value for every element in the result array. That array in this case is the canvas itself.

-

texelFetchis a texture function that looks up a single texel from a texture.It takes 3 parameters. The sampler, an integer based texel coordinate, and mip level.

gl_FragCoordis a vec2, we need to turn it into anivec2to use it withtexelFetch. There is no extra math to do here as long the source texture and destination texture are the same size which in this case they are. -

Our Shader is writing 4 values per pixel

In this particular case this affects how we read the output. We ask for

RGBA/UNSIGNED_BYTEfromreadPixelsbecause other format/type combinations are not supported. So we have to look at every 4th value for our answer.Note: It would be smart to try to take advantage of the fact that WebGL does 4 values at a time to go even faster.

-

We use

R8as our texture’s internal format.This means only the red channel from the texture has value from our data.

-

Both our input data and output data (the canvas) are

UNSIGNED_BYTEvaluesThe means we can only pass in and get back integer values between 0 and 255. We could use different formats for input by supplying a texture of a different format. We could also try rendering to a texture of a different format for more range of output values.

In the example above src and dst are the same size. Let’s change it so we add every 2 values

from src to make dst. In other words, given [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] as input we want

[3, 7, 11] as output. And further, let’s keep the source as 3x2 data

The basic formula to get a value from a 2D array as though it was a 1D array is

y = floor(indexInto1DArray / widthOf2DArray);

x = indexInto1DArray % widthOf2Array;

Given that, our fragment shader needs to change to this to add every 2 values.

#version 300 es

precision highp float;

uniform sampler2D srcTex;

uniform ivec2 dstDimensions;

out vec4 outColor;

vec4 getValueFrom2DTextureAs1DArray(sampler2D tex, ivec2 dimensions, int index) {

int y = index / dimensions.x;

int x = index % dimensions.x;

return texelFetch(tex, ivec2(x, y), 0);

}

void main() {

// compute a 1D index into dst

ivec2 dstPixel = ivec2(gl_FragCoord.xy);

int dstIndex = dstPixel.y * dstDimensions.x + dstPixel.x;

ivec2 srcDimensions = textureSize(srcTex, 0); // size of mip 0

vec4 v1 = getValueFrom2DTextureAs1DArray(srcTex, srcDimensions, dstIndex * 2);

vec4 v2 = getValueFrom2DTextureAs1DArray(srcTex, srcDimensions, dstIndex * 2 + 1);

outColor = v1 + v2;

}

The function getValueFrom2DTextureAs1DArray is basically our array accessor

function. That means these 2 lines

vec4 v1 = getValueFrom2DTextureAs1DArray(srcTex, srcDimensions, dstIndex * 2.0);

vec4 v2 = getValueFrom2DTextureAs1DArray(srcTex, srcDimensions, dstIndex * 2.0 + 1.0);

Effectively mean this

vec4 v1 = srcTexAs1DArray[dstIndex * 2.0];

vec4 v2 = setTexAs1DArray[dstIndex * 2.0 + 1.0];

In our JavaScript we need to lookup the location of dstDimensions

const program = webglUtils.createProgramFromSources(gl, [vs, fs]);

const positionLoc = gl.getAttribLocation(program, 'position');

const srcTexLoc = gl.getUniformLocation(program, 'srcTex');

+const dstDimensionsLoc = gl.getUniformLocation(program, 'dstDimensions');

and set it

gl.useProgram(program);

gl.uniform1i(srcTexLoc, 0); // tell the shader the src texture is on texture unit 0

+gl.uniform2f(dstDimensionsLoc, dstWidth, dstHeight);

and we need to change the size of the destination (the canvas)

const dstWidth = 3;

-const dstHeight = 2;

+const dstHeight = 1;

and with that we have now have the result array able to do math with random access into the source array

If you wanted to use more arrays as input just add more textures to put more data in the same texture.

Now let’s do it with transform feedback

“Transform Feedback” is a fancy name for the ability to write the output of varyings in a vertex shader to one or more buffers.

The advantage to using transform feedback is the output is 1D

so it’s probably easier to reason about. It’s even closer to map from JavaScript.

Let’s take in 2 arrays of values and output their sum, their difference, and their product. Here’s the vertex shader

#version 300 es

in float a;

in float b;

out float sum;

out float difference;

out float product;

void main() {

sum = a + b;

difference = a - b;

product = a * b;

}

and the fragment shader is just enough to compile

#version 300 es

precision highp float;

void main() {

}

To use transform feedback we have to tell WebGL which varyings we want written

and in what order. We do that by calling gl.transformFeedbackVaryings before

linking the shader program. Because of this we are not going to use our helper

to compile the shaders and link the program this time, just to make it clear

what we have to do.

So, here is the code for compiling a shader similar to the code in the very first article.

function createShader(gl, type, src) {

const shader = gl.createShader(type);

gl.shaderSource(shader, src);

gl.compileShader(shader);

if (!gl.getShaderParameter(shader, gl.COMPILE_STATUS)) {

throw new Error(gl.getShaderInfoLog(shader));

}

return shader;

}

We’ll use it to compile our 2 shaders and then attach them and call

gl.transformFeedbackVaryings before linking

const vShader = createShader(gl, gl.VERTEX_SHADER, vs);

const fShader = createShader(gl, gl.FRAGMENT_SHADER, fs);

const program = gl.createProgram();

gl.attachShader(program, vShader);

gl.attachShader(program, fShader);

gl.transformFeedbackVaryings(

program,

['sum', 'difference', 'product'],

gl.SEPARATE_ATTRIBS,

);

gl.linkProgram(program);

if (!gl.getProgramParameter(program, gl.LINK_STATUS)) {

throw new Error(gl.getProgramInfoLog(program));

}

gl.transformFeedbackVaryings takes 3 arguments. The program, an array of the names

of the varyings we want to write in the order you want them written.

If you did have a fragment shader that actually did

something then maybe some of your varyings are only for the fragment shader and so

don’t need to be written. In our case we will write all of our varyings so we pass

in the names of all 3. The last parameter can be 1 of 2 values. Either SEPARATE_ATTRIBS

or INTERLEAVED_ATTRIBS.

SEPARATE_ATTRIBS means each varying will be written to a different buffer.

INTERLEAVED_ATTRIBS means all the varyings will be written to the same buffer

but interleaved on the order we specified. In our case since we specified

['sum', 'difference', 'product'] if we used INTERLEAVED_ATTRIBS the output

would be sum0, difference0, product0, sum1, difference1, product1, sum2, difference2, product2, etc...

into a single buffer. We’re using SEPARATE_ATTRIBS though so instead

each output will be written to the a different buffer.

So, like other examples we need to setup buffers for our input attributes

const aLoc = gl.getAttribLocation(program, 'a');

const bLoc = gl.getAttribLocation(program, 'b');

// Create a vertex array object (attribute state)

const vao = gl.createVertexArray();

gl.bindVertexArray(vao);

function makeBuffer(gl, sizeOrData) {

const buf = gl.createBuffer();

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, buf);

gl.bufferData(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, sizeOrData, gl.STATIC_DRAW);

return buf;

}

function makeBufferAndSetAttribute(gl, data, loc) {

const buf = makeBuffer(gl, data);

// setup our attributes to tell WebGL how to pull

// the data from the buffer above to the attribute

gl.enableVertexAttribArray(loc);

gl.vertexAttribPointer(

loc,

1, // size (num components)

gl.FLOAT, // type of data in buffer

false, // normalize

0, // stride (0 = auto)

0, // offset

);

}

const a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];

const b = [3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18];

// put data in buffers

const aBuffer = makeBufferAndSetAttribute(gl, new Float32Array(a), aLoc);

const bBuffer = makeBufferAndSetAttribute(gl, new Float32Array(b), bLoc);

Then we need to setup a “transform feedback”. A “transform feedback” is an object that contains the state of the buffers we will write to. Whereas an vertex array specifies the state of all the input attributes, a “transform feedback” contains the state of all the output attributes.

Here is the code to set ours up

// Create and fill out a transform feedback

const tf = gl.createTransformFeedback();

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, tf);

// make buffers for output

const sumBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, a.length * 4);

const differenceBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, a.length * 4);

const productBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, a.length * 4);

// bind the buffers to the transform feedback

gl.bindBufferBase(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER, 0, sumBuffer);

gl.bindBufferBase(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER, 1, differenceBuffer);

gl.bindBufferBase(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER, 2, productBuffer);

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, null);

// buffer's we are writing to can not be bound else where

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, null); // productBuffer was still bound to ARRAY_BUFFER so unbind it

We call bindBufferBase to set which buffer, each of the outputs, output 0, output 1, and output 2

will write to. Outputs 0, 1, 2 correspond to the names we passed to gl.transformFeedbackVaryings

when we linked the program.

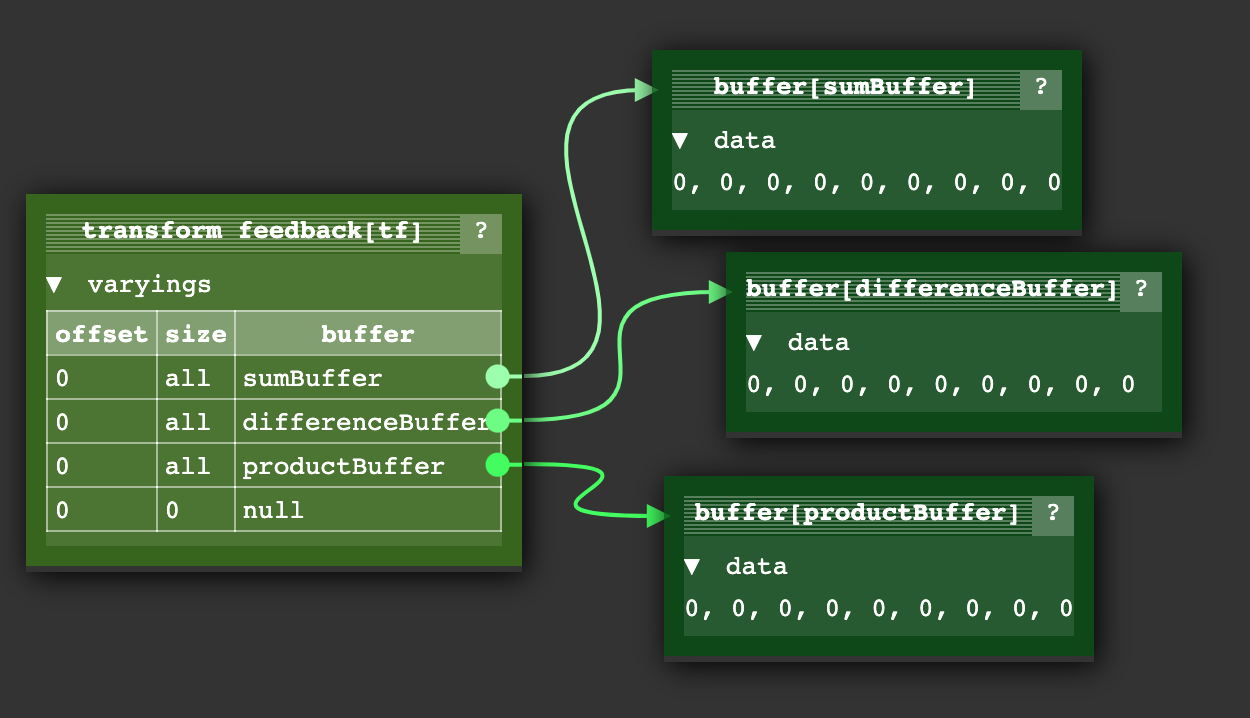

When we’re done the “transform feedback” we created has state like this

There is also a function bindBufferRange that lets us specify a sub range within a buffer where

we will write to but we won’t use that here.

So to execute the shader we do this

gl.useProgram(program);

// bind our input attribute state for the a and b buffers

gl.bindVertexArray(vao);

// no need to call the fragment shader

gl.enable(gl.RASTERIZER_DISCARD);

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, tf);

gl.beginTransformFeedback(gl.POINTS);

gl.drawArrays(gl.POINTS, 0, a.length);

gl.endTransformFeedback();

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, null);

// turn on using fragment shaders again

gl.disable(gl.RASTERIZER_DISCARD);

We turn off calling the fragment shader. We bind the transform feedback object we created earlier, we turn on transform feedback, then we call draw.

To look at the values we can call gl.getBufferSubData

log(`a: ${a}`);

log(`b: ${b}`);

printResults(gl, sumBuffer, 'sums');

printResults(gl, differenceBuffer, 'differences');

printResults(gl, productBuffer, 'products');

function printResults(gl, buffer, label) {

const results = new Float32Array(a.length);

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, buffer);

gl.getBufferSubData(

gl.ARRAY_BUFFER,

0, // byte offset into GPU buffer,

results,

);

// print the results

log(`${label}: ${results}`);

}

You can see it worked. We got the GPU to compute the sum, difference, and product of the ‘a’ and ‘b’ values we passed in.

Note: You might find this state diagram transform feedback example helpful in visualizing what a “transform feedback” is. It’s not the same example as above though. The vertex shader it uses with transform feedback generates positions and colors for a circle of points.

First example: particles

Let’s say you have a very simple particle system. Every particle just has a position and a velocity and if it goes off one edge of the screen it wraps around to the other side.

Given most of the other articles on this site you’d update the positions of the particles in JavaScript

for (const particle of particles) {

particle.pos.x = (particle.pos.x + particle.velocity.x) % canvas.width;

particle.pos.y = (particle.pos.y + particle.velocity.y) % canvas.height;

}

and then draw the particles either one at a time

useProgram (particleShader)

setup particle attributes

for each particle

set uniforms

draw particle

Or you might upload all the new particle positions

bindBuffer(..., particlePositionBuffer)

bufferData(..., latestParticlePositions, ...)

useProgram (particleShader)

setup particle attributes

set uniforms

draw particles

Using the transform feedback example above we could make a buffer with the velocity for each particle. Then we could make 2 buffers for the positions. We’d use transform feedback to add the velocity to one position buffer and write it to the other position buffer. Then we’d draw with the new positions. On the next frame we’d read from the buffer with the new positions and write back to the other buffer to generate newer positions.

Here’s the vertex shader to update the particle positions

#version 300 es

in vec2 oldPosition;

in vec2 velocity;

uniform float deltaTime;

uniform vec2 canvasDimensions;

out vec2 newPosition;

vec2 euclideanModulo(vec2 n, vec2 m) {

return mod(mod(n, m) + m, m);

}

void main() {

newPosition = euclideanModulo(

oldPosition + velocity * deltaTime,

canvasDimensions);

}

To draw the particles we’ll just use a simple vertex shader

#version 300 es

in vec4 position;

uniform mat4 matrix;

void main() {

// do the common matrix math

gl_Position = matrix * position;

gl_PointSize = 10.0;

}

Let’s turn the code for creating and linking a program into a function we can use for both shaders

function createProgram(gl, shaderSources, transformFeedbackVaryings) {

const program = gl.createProgram();

[gl.VERTEX_SHADER, gl.FRAGMENT_SHADER].forEach((type, ndx) => {

const shader = createShader(gl, type, shaderSources[ndx]);

gl.attachShader(program, shader);

});

if (transformFeedbackVaryings) {

gl.transformFeedbackVaryings(

program,

transformFeedbackVaryings,

gl.SEPARATE_ATTRIBS,

);

}

gl.linkProgram(program);

if (!gl.getProgramParameter(program, gl.LINK_STATUS)) {

throw new Error(gl.getProgramInfoLog(program));

}

return program;

}

and then use it to compile the shaders, one with a transform feedback varying.

const updatePositionProgram = createProgram(

gl, [updatePositionVS, updatePositionFS], ['newPosition']);

const drawParticlesProgram = createProgram(

gl, [drawParticlesVS, drawParticlesFS]);

As usual we need to lookup locations

const updatePositionPrgLocs = {

oldPosition: gl.getAttribLocation(updatePositionProgram, 'oldPosition'),

velocity: gl.getAttribLocation(updatePositionProgram, 'velocity'),

canvasDimensions: gl.getUniformLocation(updatePositionProgram, 'canvasDimensions'),

deltaTime: gl.getUniformLocation(updatePositionProgram, 'deltaTime'),

};

const drawParticlesProgLocs = {

position: gl.getAttribLocation(drawParticlesProgram, 'position'),

matrix: gl.getUniformLocation(drawParticlesProgram, 'matrix'),

};

Now let’s make some random positions and velocities

// create random positions and velocities.

const rand = (min, max) => {

if (max === undefined) {

max = min;

min = 0;

}

return Math.random() * (max - min) + min;

};

const numParticles = 200;

const createPoints = (num, ranges) =>

new Array(num).fill(0).map(_ => ranges.map(range => rand(...range))).flat();

const positions = new Float32Array(createPoints(numParticles, [[canvas.width], [canvas.height]]));

const velocities = new Float32Array(createPoints(numParticles, [[-300, 300], [-300, 300]]));

Then we’ll put those into buffers.

function makeBuffer(gl, sizeOrData, usage) {

const buf = gl.createBuffer();

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, buf);

gl.bufferData(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, sizeOrData, usage);

return buf;

}

const position1Buffer = makeBuffer(gl, positions, gl.DYNAMIC_DRAW);

const position2Buffer = makeBuffer(gl, positions, gl.DYNAMIC_DRAW);

const velocityBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, velocities, gl.STATIC_DRAW);

Note that we passed in gl.DYNAMIC_DRAW to gl.bufferData for the 2 position buffers

since we’ll be updating them often. This is just a hint to WebGL for optimization.

Whether it has any effect on performance is up to WebGL.

We need 4 vertex arrays.

- 1 for using

position1Bufferandvelocitywhen updating positions - 1 for using

position2Bufferandvelocitywhen updating positions - 1 for using

position1Bufferwhen drawing - 1 for using

position2Bufferwhen drawing

function makeVertexArray(gl, bufLocPairs) {

const va = gl.createVertexArray();

gl.bindVertexArray(va);

for (const [buffer, loc] of bufLocPairs) {

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, buffer);

gl.enableVertexAttribArray(loc);

gl.vertexAttribPointer(

loc, // attribute location

2, // number of elements

gl.FLOAT, // type of data

false, // normalize

0, // stride (0 = auto)

0, // offset

);

}

return va;

}

const updatePositionVA1 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

[position1Buffer, updatePositionPrgLocs.oldPosition],

[velocityBuffer, updatePositionPrgLocs.velocity],

]);

const updatePositionVA2 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

[position2Buffer, updatePositionPrgLocs.oldPosition],

[velocityBuffer, updatePositionPrgLocs.velocity],

]);

const drawVA1 = makeVertexArray(

gl, [[position1Buffer, drawParticlesProgLocs.position]]);

const drawVA2 = makeVertexArray(

gl, [[position2Buffer, drawParticlesProgLocs.position]]);

We then make 2 transform feedback objects.

- 1 for writing to

position1Buffer - 1 for writing to

position2Buffer

function makeTransformFeedback(gl, buffer) {

const tf = gl.createTransformFeedback();

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, tf);

gl.bindBufferBase(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER, 0, buffer);

return tf;

}

const tf1 = makeTransformFeedback(gl, position1Buffer);

const tf2 = makeTransformFeedback(gl, position2Buffer);

When using transform feedback it’s important to unbind buffers

from other bind points. ARRAY_BUFFER still has the last buffer

bound that we put data in. TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER is set when

calling gl.bindBufferBase. That is a little confusing. Calling

gl.bindBufferBase with TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER actually

binds the buffer to 2 places. One, to indexed bind point inside

the transform feedback object. The other is to a kind of global

bind point called TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER.

// unbind left over stuff

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, null);

gl.bindBuffer(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER, null);

So that we can easily swap updating and drawing buffers we’ll setup these 2 objects

let current = {

updateVA: updatePositionVA1, // read from position1

tf: tf2, // write to position2

drawVA: drawVA2, // draw with position2

};

let next = {

updateVA: updatePositionVA2, // read from position2

tf: tf1, // write to position1

drawVA: drawVA1, // draw with position1

};

Then we’ll do a render loop, first we’ll update the positions using transform feedback.

let then = 0;

function render(time) {

// convert to seconds

time *= 0.001;

// Subtract the previous time from the current time

const deltaTime = time - then;

// Remember the current time for the next frame.

then = time;

webglUtils.resizeCanvasToDisplaySize(gl.canvas);

gl.clear(gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

// compute the new positions

gl.useProgram(updatePositionProgram);

gl.bindVertexArray(current.updateVA);

gl.uniform2f(updatePositionPrgLocs.canvasDimensions, gl.canvas.width, gl.canvas.height);

gl.uniform1f(updatePositionPrgLocs.deltaTime, deltaTime);

// turn of using the fragment shader

gl.enable(gl.RASTERIZER_DISCARD);

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, current.tf);

gl.beginTransformFeedback(gl.POINTS);

gl.drawArrays(gl.POINTS, 0, numParticles);

gl.endTransformFeedback();

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, null);

// turn on using fragment shaders again

gl.disable(gl.RASTERIZER_DISCARD);

and then draw the particles

// now draw the particles.

gl.useProgram(drawParticlesProgram);

gl.bindVertexArray(current.drawVA);

gl.viewport(0, 0, gl.canvas.width, gl.canvas.height);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(

drawParticlesProgLocs.matrix,

false,

m4.orthographic(0, gl.canvas.width, 0, gl.canvas.height, -1, 1));

gl.drawArrays(gl.POINTS, 0, numParticles);

and finally swap current and next so that next frame we’ll

use the latest positions to generate new ones

// swap which buffer we will read from

// and which one we will write to

{

const temp = current;

current = next;

next = temp;

}

requestAnimationFrame(render);

}

requestAnimationFrame(render);

And with that we have simple GPU based particles.

Next Example: Finding the closest line segment to a point

I’m not sure this is a good example but it’s the one I wrote. I say it might not be good because I suspect there are better algorithms for finding the closest line to a point than brute force checking every line with the point. For example various space partitioning algorithms might let you easily discard 95% of the points and so be faster. Still, this example probably does show some techniques of GPGPU at least.

The problem: We have 500 points and 1000 line segments. For each point find which line segment it is closest to. The brute force method is

for each point

minDistanceSoFar = MAX_VALUE

for each line segment

compute distance from point to line segment

if distance is < minDistanceSoFar

minDistanceSoFar = distance

closestLine = line segment

For 500 points each checking 1000 lines that’s 500,000 checks. Modern GPUs have 100s or 1000s of cores so if we could do this on the GPU we could potentially run hundreds or thousands of times faster.

This time, while we can put the points in a buffer like we did for the particles we can’t put the line segments in a buffer. Buffers supply their data via attributes. That means we can’t randomly access any value on demand, instead the values are assigned to the attribute outside the shader’s control.

So, we need to put the line positions in a texture, which as we pointed out above is another word for a 2D array though we can still treat that 2D array as a 1D array if we want.

Here’s the vertex shader that finds the closest line for a single point. It’s exactly the brute force algorithm as above

const closestLineVS = `#version 300 es

in vec3 point;

uniform sampler2D linesTex;

uniform int numLineSegments;

flat out int closestNdx;

vec4 getAs1D(sampler2D tex, ivec2 dimensions, int index) {

int y = index / dimensions.x;

int x = index % dimensions.x;

return texelFetch(tex, ivec2(x, y), 0);

}

// from https://stackoverflow.com/a/6853926/128511

// a is the point, b,c is the line segment

float distanceFromPointToLine(in vec3 a, in vec3 b, in vec3 c) {

vec3 ba = a - b;

vec3 bc = c - b;

float d = dot(ba, bc);

float len = length(bc);

float param = 0.0;

if (len != 0.0) {

param = clamp(d / (len * len), 0.0, 1.0);

}

vec3 r = b + bc * param;

return distance(a, r);

}

void main() {

ivec2 linesTexDimensions = textureSize(linesTex, 0);

// find the closest line segment

float minDist = 10000000.0;

int minIndex = -1;

for (int i = 0; i < numLineSegments; ++i) {

vec3 lineStart = getAs1D(linesTex, linesTexDimensions, i * 2).xyz;

vec3 lineEnd = getAs1D(linesTex, linesTexDimensions, i * 2 + 1).xyz;

float dist = distanceFromPointToLine(point, lineStart, lineEnd);

if (dist < minDist) {

minDist = dist;

minIndex = i;

}

}

closestNdx = minIndex;

}

`;

I renamed getValueFrom2DTextureAs1DArray to getAs1D just to make

some of the lines shorter and more readable.

Otherwise it’s a pretty straight forward implementation of the brute force algorithm

we wrote above.

point is the current point. linesTex contains the points for the

line segment in pairs, first point, followed by second point.

First let’s make some test data. Here’s 2 points and 5 lines. They are padded with 0, 0 because each one will stored in an RGBA texture.

const points = [

100, 100,

200, 100,

];

const lines = [

25, 50,

25, 150,

90, 50,

90, 150,

125, 50,

125, 150,

185, 50,

185, 150,

225, 50,

225, 150,

];

const numPoints = points.length / 2;

const numLineSegments = lines.length / 2 / 2;

If we plot those out they look like this

The lines are numbered 0 to 4 from left to right, so if our code works the first point (red) should get a value of 1 as the closest line, the second point (green), should get a value of 3.

Lets put the points in a buffer as well as make a buffer to hold the computed closest index for each

const closestNdxBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, points.length * 4, gl.STATIC_DRAW);

const pointsBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, new Float32Array(points), gl.DYNAMIC_DRAW);

and lets make a texture to hold all the end points of the lines.

function createDataTexture(gl, data, numComponents, internalFormat, format, type) {

const numElements = data.length / numComponents;

// compute a size that will hold all of our data

const width = Math.ceil(Math.sqrt(numElements));

const height = Math.ceil(numElements / width);

const bin = new Float32Array(width * height * numComponents);

bin.set(data);

const tex = gl.createTexture();

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, tex);

gl.texImage2D(

gl.TEXTURE_2D,

0, // mip level

internalFormat,

width,

height,

0, // border

format,

type,

bin,

);

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_MIN_FILTER, gl.NEAREST);

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_MAG_FILTER, gl.NEAREST);

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_WRAP_S, gl.CLAMP_TO_EDGE);

gl.texParameteri(gl.TEXTURE_2D, gl.TEXTURE_WRAP_T, gl.CLAMP_TO_EDGE);

return {tex, dimensions: [width, height]};

}

const {tex: linesTex, dimensions: linesTexDimensions} =

createDataTexture(gl, lines, 2, gl.RG32F, gl.RG, gl.FLOAT);

In this case we’re letting the code choose the dimensions of the texture and letting it pad the texture out. For example if we gave it an array with 7 entries it would stick that in a 3x3 texture. It returns both the texture and the dimensions it chose. Why do we let it choose the dimension? Because textures have a maximum dimension.

Ideally we’d just like to look at our data as a 1 dimensional array of positions, 1 dimensional array of line points etc. So we could just declare a texture to be Nx1. Unfortunately GPUs have a maximum dimension and that can be as low as 1024 or 2048. If the limit was 1024 and we needed 1025 values in our array we’d have to put the data in a texture like say 512x2. By putting the data in a square we won’t hit the limit until we hit the maximum texture dimension squared. For a dimension limit of 1024 that would allow arrays of over 1 million values.

Next up compile the shader and look up the locations

const closestLinePrg = createProgram(

gl, [closestLineVS, closestLineFS], ['closestNdx']);

const closestLinePrgLocs = {

point: gl.getAttribLocation(closestLinePrg, 'point'),

linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(closestLinePrg, 'linesTex'),

numLineSegments: gl.getUniformLocation(closestLinePrg, 'numLineSegments'),

};

And make a vertex array for the points

function makeVertexArray(gl, bufLocPairs) {

const va = gl.createVertexArray();

gl.bindVertexArray(va);

for (const [buffer, loc] of bufLocPairs) {

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, buffer);

gl.enableVertexAttribArray(loc);

gl.vertexAttribPointer(

loc, // attribute location

2, // number of elements

gl.FLOAT, // type of data

false, // normalize

0, // stride (0 = auto)

0, // offset

);

}

return va;

}

const closestLinesVA = makeVertexArray(gl, [

[pointsBuffer, closestLinePrgLocs.point],

]);

Now we need to setup a transform feedback to let us write the results to the

cloestNdxBuffer.

function makeTransformFeedback(gl, buffer) {

const tf = gl.createTransformFeedback();

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, tf);

gl.bindBufferBase(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER, 0, buffer);

return tf;

}

const closestNdxTF = makeTransformFeedback(gl, closestNdxBuffer);

With all of that setup we can render

// compute the closest lines

gl.bindVertexArray(closestLinesVA);

gl.useProgram(closestLinePrg);

gl.uniform1i(closestLinePrgLocs.linesTex, 0);

gl.uniform1i(closestLinePrgLocs.numLineSegments, numLineSegments);

// turn of using the fragment shader

gl.enable(gl.RASTERIZER_DISCARD);

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, closestNdxTF);

gl.beginTransformFeedback(gl.POINTS);

gl.drawArrays(gl.POINTS, 0, numPoints);

gl.endTransformFeedback();

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, null);

// turn on using fragment shaders again

gl.disable(gl.RASTERIZER_DISCARD);

and finally read the result

// get the results.

{

const results = new Int32Array(numPoints);

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, closestNdxBuffer);

gl.getBufferSubData(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, 0, results);

log(results);

}

If we run it

We should get the expected result of [1, 3]

Reading data back from the GPU is slow. Let’s say we wanted to visualize the results. It would be pretty easy to read those results back to JavaScript and draw them but how about without reading them back to JavaScript? Let’s use the data as is and draw the results?

First, drawing the points is relatively easy. It’s the same as the particle example Let’s draw each point in a different color so we can highlight the closest line in the same color.

const drawPointsVS = `#version 300 es

in vec4 point;

uniform float numPoints;

uniform mat4 matrix;

out vec4 v_color;

// converts hue, saturation, and value each in the 0 to 1 range

// to rgb. c = color, c.x = hue, c.y = saturation, c.z = value

vec3 hsv2rgb(vec3 c) {

c = vec3(c.x, clamp(c.yz, 0.0, 1.0));

vec4 K = vec4(1.0, 2.0 / 3.0, 1.0 / 3.0, 3.0);

vec3 p = abs(fract(c.xxx + K.xyz) * 6.0 - K.www);

return c.z * mix(K.xxx, clamp(p - K.xxx, 0.0, 1.0), c.y);

}

void main() {

gl_Position = matrix * point;

gl_PointSize = 10.0;

float hue = float(gl_VertexID) / numPoints;

v_color = vec4(hsv2rgb(vec3(hue, 1, 1)), 1);

}

`;

const drawClosestLinesPointsFS = `#version 300 es

precision highp float;

in vec4 v_color;

out vec4 outColor;

void main() {

outColor = v_color;

}`;

Rather than passing in colors we generate them using hsv2rgb and passing it

a hue from to 0 to 1. For 500 points there would

be no easy way to tell lines apart but for around 10 points we should be

able to distinguish them.

We pass the generated color to a simple fragment shader

const drawClosestPointsLinesFS = `

precision highp float;

varying vec4 v_color;

void main() {

gl_FragColor = v_color;

}

`;

To draw all the lines, even the ones that are not close to any points is almost the same except we don’t generate a color. In this case we’re just using a hardcoded color.

const drawLinesVS = `#version 300 es

uniform sampler2D linesTex;

uniform mat4 matrix;

out vec4 v_color;

vec4 getAs1D(sampler2D tex, ivec2 dimensions, int index) {

int y = index / dimensions.x;

int x = index % dimensions.x;

return texelFetch(tex, ivec2(x, y), 0);

}

void main() {

ivec2 linesTexDimensions = textureSize(linesTex, 0);

// pull the position from the texture

vec4 position = getAs1D(linesTex, linesTexDimensions, gl_VertexID);

// do the common matrix math

gl_Position = matrix * vec4(position.xy, 0, 1);

// just so we can use the same fragment shader

v_color = vec4(0.8, 0.8, 0.8, 1);

}

`;

We don’t have any attributes. We just use gl_VertexID like we covered in

the article on drawing without data.

Finally drawing closest lines works like this

const drawClosestLinesVS = `#version 300 es

in int closestNdx;

uniform float numPoints;

uniform sampler2D linesTex;

uniform mat4 matrix;

out vec4 v_color;

vec4 getAs1D(sampler2D tex, ivec2 dimensions, int index) {

int y = index / dimensions.x;

int x = index % dimensions.x;

return texelFetch(tex, ivec2(x, y), 0);

}

// converts hue, saturation, and value each in the 0 to 1 range

// to rgb. c = color, c.x = hue, c.y = saturation, c.z = value

vec3 hsv2rgb(vec3 c) {

c = vec3(c.x, clamp(c.yz, 0.0, 1.0));

vec4 K = vec4(1.0, 2.0 / 3.0, 1.0 / 3.0, 3.0);

vec3 p = abs(fract(c.xxx + K.xyz) * 6.0 - K.www);

return c.z * mix(K.xxx, clamp(p - K.xxx, 0.0, 1.0), c.y);

}

void main() {

ivec2 linesTexDimensions = textureSize(linesTex, 0);

// pull the position from the texture

int linePointId = closestNdx * 2 + gl_VertexID % 2;

vec4 position = getAs1D(linesTex, linesTexDimensions, linePointId);

// do the common matrix math

gl_Position = matrix * vec4(position.xy, 0, 1);

int pointId = gl_InstanceID;

float hue = float(pointId) / numPoints;

v_color = vec4(hsv2rgb(vec3(hue, 1, 1)), 1);

}

`;

We pass in closestNdx as an attribute. These are the results we generated.

Using that we can look up specific line. We need to draw 2 points per line

though so we’ll use instanced drawing to

draw 2 points per closestNdx. We can then use gl_VertexID % 2 to choose

the starting or ending point.

Finally we compute a color using the same method we used when drawing points so they’ll match their points.

We need to compile all of these new shader programs and look up locations

const closestLinePrg = createProgram(

gl, [closestLineVS, closestLineFS], ['closestNdx']);

+const drawLinesPrg = createProgram(

+ gl, [drawLinesVS, drawClosestLinesPointsFS]);

+const drawClosestLinesPrg = createProgram(

+ gl, [drawClosestLinesVS, drawClosestLinesPointsFS]);

+const drawPointsPrg = createProgram(

+ gl, [drawPointsVS, drawClosestLinesPointsFS]);

const closestLinePrgLocs = {

point: gl.getAttribLocation(closestLinePrg, 'point'),

linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(closestLinePrg, 'linesTex'),

numLineSegments: gl.getUniformLocation(closestLinePrg, 'numLineSegments'),

};

+const drawLinesPrgLocs = {

+ linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(drawLinesPrg, 'linesTex'),

+ matrix: gl.getUniformLocation(drawLinesPrg, 'matrix'),

+};

+const drawClosestLinesPrgLocs = {

+ closestNdx: gl.getAttribLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'closestNdx'),

+ linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'linesTex'),

+ matrix: gl.getUniformLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'matrix'),

+ numPoints: gl.getUniformLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'numPoints'),

+};

+const drawPointsPrgLocs = {

+ point: gl.getAttribLocation(drawPointsPrg, 'point'),

+ matrix: gl.getUniformLocation(drawPointsPrg, 'matrix'),

+ numPoints: gl.getUniformLocation(drawPointsPrg, 'numPoints'),

+};

We need to vertex arrays for drawing the points and the closest lines.

const closestLinesVA = makeVertexArray(gl, [

[pointsBuffer, closestLinePrgLocs.point],

]);

+const drawClosestLinesVA = gl.createVertexArray();

+gl.bindVertexArray(drawClosestLinesVA);

+gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, closestNdxBuffer);

+gl.enableVertexAttribArray(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.closestNdx);

+gl.vertexAttribIPointer(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.closestNdx, 1, gl.INT, 0, 0);

+gl.vertexAttribDivisor(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.closestNdx, 1);

+

+const drawPointsVA = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [pointsBuffer, drawPointsPrgLocs.point],

+]);

So, at render time we compute the results like we did before but

we don’t look up the results with getBufferSubData. Instead we just

pass them to the appropriate shaders.

First we draw all the lines in gray

// draw all the lines in gray

gl.bindFramebuffer(gl.FRAMEBUFFER, null);

gl.viewport(0, 0, gl.canvas.width, gl.canvas.height);

gl.bindVertexArray(null);

gl.useProgram(drawLinesPrg);

// bind the lines texture to texture unit 0

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0);

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, linesTex);

// Tell the shader to use texture on texture unit 0

gl.uniform1i(drawLinesPrgLocs.linesTex, 0);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(drawLinesPrgLocs.matrix, false, matrix);

gl.drawArrays(gl.LINES, 0, numLineSegments * 2);

Then we draw all the closest lines

gl.bindVertexArray(drawClosestLinesVA);

gl.useProgram(drawClosestLinesPrg);

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0);

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, linesTex);

gl.uniform1i(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.linesTex, 0);

gl.uniform1f(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.numPoints, numPoints);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.matrix, false, matrix);

gl.drawArraysInstanced(gl.LINES, 0, 2, numPoints);

and finally we draw each point

gl.bindVertexArray(drawPointsVA);

gl.useProgram(drawPointsPrg);

gl.uniform1f(drawPointsPrgLocs.numPoints, numPoints);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(drawPointsPrgLocs.matrix, false, matrix);

gl.drawArrays(gl.POINTS, 0, numPoints);

Before we run it lets do one more thing. Let’s add more points and lines

-const points = [

- 100, 100,

- 200, 100,

-];

-const lines = [

- 25, 50,

- 25, 150,

- 90, 50,

- 90, 150,

- 125, 50,

- 125, 150,

- 185, 50,

- 185, 150,

- 225, 50,

- 225, 150,

-];

+function createPoints(numPoints, ranges) {

+ const points = [];

+ for (let i = 0; i < numPoints; ++i) {

+ points.push(...ranges.map(range => r(...range)));

+ }

+ return points;

+}

+

+const r = (min, max) => min + Math.random() * (max - min);

+

+const points = createPoints(8, [[0, gl.canvas.width], [0, gl.canvas.height]]);

+const lines = createPoints(125 * 2, [[0, gl.canvas.width], [0, gl.canvas.height]]);

const numPoints = points.length / 2;

const numLineSegments = lines.length / 2 / 2;

and if we run that

You can bump up the number of points and lines but at some point you won’t be able to tell which points go with which lines but with a smaller number you can at least visually verify it’s working.

Just for fun, lets combine the particle example and this example. We’ll use the techniques we used to update the positions of particles to update the points. For updating the line end points we’ll do what we did at the top and write results to a texture.

To do that we copy in the updatePositionFS vertex shader

from the particle example. For the lines, since their values

are stored in a texture we need to move their points in

a fragment shader

const updateLinesVS = `#version 300 es

in vec4 position;

void main() {

gl_Position = position;

}

`;

const updateLinesFS = `#version 300 es

precision highp float;

uniform sampler2D linesTex;

uniform sampler2D velocityTex;

uniform vec2 canvasDimensions;

uniform float deltaTime;

out vec4 outColor;

vec2 euclideanModulo(vec2 n, vec2 m) {

return mod(mod(n, m) + m, m);

}

void main() {

// compute texel coord from gl_FragCoord;

ivec2 texelCoord = ivec2(gl_FragCoord.xy);

vec2 position = texelFetch(linesTex, texelCoord, 0).xy;

vec2 velocity = texelFetch(velocityTex, texelCoord, 0).xy;

vec2 newPosition = euclideanModulo(position + velocity * deltaTime, canvasDimensions);

outColor = vec4(newPosition, 0, 1);

}

`;

We can then compile the 2 new shaders for updating the points and the lines and look up locations

+const updatePositionPrg = createProgram(

+ gl, [updatePositionVS, updatePositionFS], ['newPosition']);

+const updateLinesPrg = createProgram(

+ gl, [updateLinesVS, updateLinesFS]);

const closestLinePrg = createProgram(

gl, [closestLineVS, closestLineFS], ['closestNdx']);

const drawLinesPrg = createProgram(

gl, [drawLinesVS, drawClosestLinesPointsFS]);

const drawClosestLinesPrg = createProgram(

gl, [drawClosestLinesVS, drawClosestLinesPointsFS]);

const drawPointsPrg = createProgram(

gl, [drawPointsVS, drawClosestLinesPointsFS]);

+const updatePositionPrgLocs = {

+ oldPosition: gl.getAttribLocation(updatePositionPrg, 'oldPosition'),

+ velocity: gl.getAttribLocation(updatePositionPrg, 'velocity'),

+ canvasDimensions: gl.getUniformLocation(updatePositionPrg, 'canvasDimensions'),

+ deltaTime: gl.getUniformLocation(updatePositionPrg, 'deltaTime'),

+};

+const updateLinesPrgLocs = {

+ position: gl.getAttribLocation(updateLinesPrg, 'position'),

+ linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(updateLinesPrg, 'linesTex'),

+ velocityTex: gl.getUniformLocation(updateLinesPrg, 'velocityTex'),

+ canvasDimensions: gl.getUniformLocation(updateLinesPrg, 'canvasDimensions'),

+ deltaTime: gl.getUniformLocation(updateLinesPrg, 'deltaTime'),

+};

const closestLinePrgLocs = {

point: gl.getAttribLocation(closestLinePrg, 'point'),

linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(closestLinePrg, 'linesTex'),

numLineSegments: gl.getUniformLocation(closestLinePrg, 'numLineSegments'),

};

const drawLinesPrgLocs = {

linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(drawLinesPrg, 'linesTex'),

matrix: gl.getUniformLocation(drawLinesPrg, 'matrix'),

};

const drawClosestLinesPrgLocs = {

closestNdx: gl.getAttribLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'closestNdx'),

linesTex: gl.getUniformLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'linesTex'),

matrix: gl.getUniformLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'matrix'),

numPoints: gl.getUniformLocation(drawClosestLinesPrg, 'numPoints'),

};

const drawPointsPrgLocs = {

point: gl.getAttribLocation(drawPointsPrg, 'point'),

matrix: gl.getUniformLocation(drawPointsPrg, 'matrix'),

numPoints: gl.getUniformLocation(drawPointsPrg, 'numPoints'),

};

We need to generate velocities for both the points and lines

const points = createPoints(8, [[0, gl.canvas.width], [0, gl.canvas.height]]);

const lines = createPoints(125 * 2, [[0, gl.canvas.width], [0, gl.canvas.height]]);

const numPoints = points.length / 2;

const numLineSegments = lines.length / 2 / 2;

+const pointVelocities = createPoints(numPoints, [[-20, 20], [-20, 20]]);

+const lineVelocities = createPoints(numLineSegments * 2, [[-20, 20], [-20, 20]]);

We need to make 2 buffers for points, so we can swap them like we did above for particles. We also need a buffer for the point velocities. And we need a -1 to +1 clip space quad for updating the line positions.

const closestNdxBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, points.length * 4, gl.STATIC_DRAW);

-const pointsBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, new Float32Array(points), gl.STATIC_DRAW);

+const pointsBuffer1 = makeBuffer(gl, new Float32Array(points), gl.DYNAMIC_DRAW);

+const pointsBuffer2 = makeBuffer(gl, new Float32Array(points), gl.DYNAMIC_DRAW);

+const pointVelocitiesBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, new Float32Array(pointVelocities), gl.STATIC_DRAW);

+const quadBuffer = makeBuffer(gl, new Float32Array([

+ -1, -1,

+ 1, -1,

+ -1, 1,

+ -1, 1,

+ 1, -1,

+ 1, 1,

+]), gl.STATIC_DRAW);

Similarly we now need 2 textures to hold the line end points, and we’ll update one from the other and swap. And, we need a texture to hold the velocities for the line end points as well.

-const {tex: linesTex, dimensions: linesTexDimensions} =

- createDataTexture(gl, lines, 2, gl.RG32F, gl.RG, gl.FLOAT);

+const {tex: linesTex1, dimensions: linesTexDimensions1} =

+ createDataTexture(gl, lines, 2, gl.RG32F, gl.RG, gl.FLOAT);

+const {tex: linesTex2, dimensions: linesTexDimensions2} =

+ createDataTexture(gl, lines, 2, gl.RG32F, gl.RG, gl.FLOAT);

+const {tex: lineVelocitiesTex, dimensions: lineVelocitiesTexDimensions} =

+ createDataTexture(gl, lineVelocities, 2, gl.RG32F, gl.RG, gl.FLOAT);

We need a bunch of vertex arrays.

- 2 for updating positions (one that

takes

pointsBuffer1as input and another that takespointsBuffer2as input). - 1 to hold the clip space -1 to +1 quad used when updating the lines.

- 2 to compute the closest lines (one that looks at points

in

pointsBuffer1and one that looks at points inpointsBuffer2). - 2 to draw the points (one that looks at points

in

pointsBuffer1and one that looks at points inpointsBuffer2)

+const updatePositionVA1 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [pointsBuffer1, updatePositionPrgLocs.oldPosition],

+ [pointVelocitiesBuffer, updatePositionPrgLocs.velocity],

+]);

+const updatePositionVA2 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [pointsBuffer2, updatePositionPrgLocs.oldPosition],

+ [pointVelocitiesBuffer, updatePositionPrgLocs.velocity],

+]);

+

+const updateLinesVA = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [quadBuffer, updateLinesPrgLocs.position],

+]);

-const closestLinesVA = makeVertexArray(gl, [

- [pointsBuffer, closestLinePrgLocs.point],

-]);

+const closestLinesVA1 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [pointsBuffer1, closestLinePrgLocs.point],

+]);

+const closestLinesVA2 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [pointsBuffer2, closestLinePrgLocs.point],

+]);

const drawClosestLinesVA = gl.createVertexArray();

gl.bindVertexArray(drawClosestLinesVA);

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, closestNdxBuffer);

gl.enableVertexAttribArray(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.closestNdx);

gl.vertexAttribIPointer(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.closestNdx, 1, gl.INT, 0, 0);

gl.vertexAttribDivisor(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.closestNdx, 1);

-const drawPointsVA = makeVertexArray(gl, [

- [pointsBuffer, drawPointsPrgLocs.point],

-]);

+const drawPointsVA1 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [pointsBuffer1, drawPointsPrgLocs.point],

+]);

+const drawPointsVA2 = makeVertexArray(gl, [

+ [pointsBuffer2, drawPointsPrgLocs.point],

+]);

We need 2 more transform feedbacks for updating the points

function makeTransformFeedback(gl, buffer) {

const tf = gl.createTransformFeedback();

gl.bindTransformFeedback(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK, tf);

gl.bindBufferBase(gl.TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER, 0, buffer);

return tf;

}

+const pointsTF1 = makeTransformFeedback(gl, pointsBuffer1);

+const pointsTF2 = makeTransformFeedback(gl, pointsBuffer2);

const closestNdxTF = makeTransformFeedback(gl, closestNdxBuffer);

We need to make framebuffers for updating the line points, one to

write to linesTex1 and one to write to linesTex2

function createFramebuffer(gl, tex) {

const fb = gl.createFramebuffer();

gl.bindFramebuffer(gl.FRAMEBUFFER, fb);

gl.framebufferTexture2D(gl.FRAMEBUFFER, gl.COLOR_ATTACHMENT0, gl.TEXTURE_2D, tex, 0);

return fb;

}

const linesFB1 = createFramebuffer(gl, linesTex1);

const linesFB2 = createFramebuffer(gl, linesTex2);

Because we want to write to floating point textures and that’s an optional

feature of WebGL2 we need to check if we can by checking for the

EXT_color_buffer_float extension

// Get A WebGL context

/** @type {HTMLCanvasElement} */

const canvas = document.querySelector("#canvas");

const gl = canvas.getContext("webgl2");

if (!gl) {

return;

}

+const ext = gl.getExtension('EXT_color_buffer_float');

+if (!ext) {

+ alert('need EXT_color_buffer_float');

+ return;

+}

And we need to setup some objects to track current and next so we can easily swap the things we need to swap each frame

let current = {

// for updating points

updatePositionVA: updatePositionVA1, // read from points1

pointsTF: pointsTF2, // write to points2

// for updating line endings

linesTex: linesTex1, // read from linesTex1

linesFB: linesFB2, // write to linesTex2

// for computing closest lines

closestLinesVA: closestLinesVA2, // read from points2

// for drawing all lines and closest lines

allLinesTex: linesTex2, // read from linesTex2

// for drawing points

drawPointsVA: drawPointsVA2, // read form points2

};

let next = {

// for updating points

updatePositionVA: updatePositionVA2, // read from points2

pointsTF: pointsTF1, // write to points1

// for updating line endings

linesTex: linesTex2, // read from linesTex2

linesFB: linesFB1, // write to linesTex1

// for computing closest lines

closestLinesVA: closestLinesVA1, // read from points1

// for drawing all lines and closest lines

allLinesTex: linesTex1, // read from linesTex1

// for drawing points

drawPointsVA: drawPointsVA1, // read form points1

};

Then we need a render loop. Let’s break all the parts into functions

let then = 0;

function render(time) {

// convert to seconds

time *= 0.001;

// Subtract the previous time from the current time

const deltaTime = time - then;

// Remember the current time for the next frame.

then = time;

webglUtils.resizeCanvasToDisplaySize(gl.canvas);

gl.clear(gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

updatePointPositions(deltaTime);

updateLineEndPoints(deltaTime);

computeClosestLines();

const matrix = m4.orthographic(0, gl.canvas.width, 0, gl.canvas.height, -1, 1);

drawAllLines(matrix);

drawClosestLines(matrix);

drawPoints(matrix);

// swap

{

const temp = current;

current = next;

next = temp;

}

requestAnimationFrame(render);

}

requestAnimationFrame(render);

}

And now we can just fill in the parts. All the previous parts

are the same example we reference current at the appropriate places.

function computeClosestLines() {

- gl.bindVertexArray(closestLinesVA);

+ gl.bindVertexArray(current.closestLinesVA);

gl.useProgram(closestLinePrg);

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0);

- gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, linesTex);

+ gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, current.linesTex);

gl.uniform1i(closestLinePrgLocs.linesTex, 0);

gl.uniform1i(closestLinePrgLocs.numLineSegments, numLineSegments);

drawArraysWithTransformFeedback(gl, closestNdxTF, gl.POINTS, numPoints);

}

function drawAllLines(matrix) {

gl.bindFramebuffer(gl.FRAMEBUFFER, null);

gl.viewport(0, 0, gl.canvas.width, gl.canvas.height);

gl.bindVertexArray(null);

gl.useProgram(drawLinesPrg);

// bind the lines texture to texture unit 0

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0);

- gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, linesTex);

+ gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, current.allLinesTex);

// Tell the shader to use texture on texture unit 0

gl.uniform1i(drawLinesPrgLocs.linesTex, 0);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(drawLinesPrgLocs.matrix, false, matrix);

gl.drawArrays(gl.LINES, 0, numLineSegments * 2);

}

function drawClosestLines(matrix) {

gl.bindVertexArray(drawClosestLinesVA);

gl.useProgram(drawClosestLinesPrg);

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0);

- gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, linesTex);

+ gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, current.allLinesTex);

gl.uniform1i(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.linesTex, 0);

gl.uniform1f(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.numPoints, numPoints);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(drawClosestLinesPrgLocs.matrix, false, matrix);

gl.drawArraysInstanced(gl.LINES, 0, 2, numPoints);

}

function drawPoints(matrix) {

- gl.bindVertexArray(drawPointsVA);

+ gl.bindVertexArray(current.drawPointsVA);

gl.useProgram(drawPointsPrg);

gl.uniform1f(drawPointsPrgLocs.numPoints, numPoints);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(drawPointsPrgLocs.matrix, false, matrix);

gl.drawArrays(gl.POINTS, 0, numPoints);

}

And we need 2 new functions for updating the points and lines

function updatePointPositions(deltaTime) {

gl.bindVertexArray(current.updatePositionVA);

gl.useProgram(updatePositionPrg);

gl.uniform1f(updatePositionPrgLocs.deltaTime, deltaTime);

gl.uniform2f(updatePositionPrgLocs.canvasDimensions, gl.canvas.width, gl.canvas.height);

drawArraysWithTransformFeedback(gl, current.pointsTF, gl.POINTS, numPoints);

}

function updateLineEndPoints(deltaTime) {

// Update the line endpoint positions ---------------------

gl.bindVertexArray(updateLinesVA); // just a quad

gl.useProgram(updateLinesPrg);

// bind texture to texture units 0 and 1

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0);

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, current.linesTex);

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0 + 1);

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, lineVelocitiesTex);

// tell the shader to look at the textures on texture units 0 and 1

gl.uniform1i(updateLinesPrgLocs.linesTex, 0);

gl.uniform1i(updateLinesPrgLocs.velocityTex, 1);

gl.uniform1f(updateLinesPrgLocs.deltaTime, deltaTime);

gl.uniform2f(updateLinesPrgLocs.canvasDimensions, gl.canvas.width, gl.canvas.height);

// write to the other lines texture

gl.bindFramebuffer(gl.FRAMEBUFFER, current.linesFB);

gl.viewport(0, 0, ...lineVelocitiesTexDimensions);

// drawing a clip space -1 to +1 quad = map over entire destination array

gl.drawArrays(gl.TRIANGLES, 0, 6);

}

And with that we can see it working dynamically and all the computation is happening on the GPU

Some Caveats about GPGPU

-

GPGPU in WebGL1 is mostly limited to using 2D arrays as output (textures). WebGL2 adds the ability to just process a 1D array of arbitrary size via transform feedback.

If you’re curious see the same article for webgl1 to see how all of these were done using only the ability to output to textures. Of course with a little thought that should be obvious.

WebGL2 versions using textures instead of transform feedback are available as well since using

texelFetchand having more texture formats available slightly changes their implementations. -

GPUs don’t have the same precision as CPUs.

Check your results and make sure they are acceptable.

-

There is overhead to GPGPU.

In the first few examples above we computed some data using WebGL and then read the results. Setting up buffers and textures, setting attributes and uniforms takes time. Enough time that for anything under a certain size it would be better to just do it in JavaScript. The actual examples multiplying 6 numbers or adding 3 pairs of numbers are much too small for GPGPU to be useful. Where that trade off is is undefined. Experiment but just a guess that if you’re not doing at least 1000 or more things keep it in JavaScript

-

readPixelsandgetBufferSubDataare slowReading the results from WebGL is slow so it’s important to avoid it as much as possible. As an example neither the particle system above nor the dynamic closest lines example ever read the results back to JavaScript. Where you can, keep the results on the GPU for as long as possible. In other words, you could do something like

- compute stuff on GPU

- read result

- prep result for next step

- upload prepped result to gpu

- compute stuff on GPU

- read result

- prep result for next step

- upload prepped result to gpu

- compute stuff on GPU

- read result

whereas via creative solutions it would be much faster if you could

- compute stuff on GPU

- prep result for next step using GPU

- compute stuff on GPU

- prep result for next step using GPU

- compute stuff on GPU

- read result

Our dynamic closest lines example did this. The results never leave the GPU.

As another example I once wrote a histogram computing shader. I then read the results back into JavaScript, figured out the min and max values Then drew the image back to the canvas using those min and max values as uniforms to auto-level the image.

But, it turned instead of reading the histogram back into JavaScript I could instead run a shader on the histogram itself that generated a 2 pixel texture with the min and max values in the texture.

I could then pass that 2 pixel texture into the 3rd shader which it could read for the min and max values. No need to read them out of the GPU for setting uniforms.

Similarly to display the histogram itself I first read the histogram data from the GPU but later I instead wrote a shader that could visualize the histogram data directly removing the need to read it back to JavaScript.

By doing that the entire process stayed on the GPU and was likely much faster.

-

GPUs can do many things in parallel but most can’t multi-task the same way a CPU can. GPUs usually can’t do “preemptive multitasking”. That means if you give them a very complex shader that say takes 5 minutes to run they’ll potentially freeze your entire machine for 5 minutes. Most well made OSes deal with this by having the CPU check how long it’s been since the last command they gave to the GPU. If it’s been too long (5-6 second) and the GPU has not responded then their only option is to reset the GPU.

This is one reason why WebGL can lose the context and you get an “Aw, rats!” or similar message.

It’s easy to give the GPU too much to do but in graphics it’s not that common to take it to the 5-6 second level. It’s usually more like the 0.1 second level which is still bad but usually you want graphics to run fast and so the programmer will hopefully optimize or find a different technique to keep the their app responsive.

GPGPU on the other hand you might truly want to give the GPU a heavy task to run. There is no easy solution here. A mobile phone has a much less powerful GPU than a top end PC. Other than doing your own timing there is no way to know for sure how much work you can give a GPU before its “too slow”

I don’t have a solution to offer. Only a warning that depending on what you’re trying to do you may run into that issue.

-

Mobile devices don’t generally support rendering to floating point textures

There are various ways of working around the issue. One use you can use the GLSL functions

floatBitsToInt,floatBitsToUint,IntBitsToFloat, andUintBitsToFloat.As an example, the texture based version of the particle example needs to write to floating point textures. We could fix it so it doesn’t require them by declaring our texture to be type

RG32I(32 integer textures) but still upload floats.In the shader we’d need to read the textures as integers and decode them to floats and then encode the result back into integers. For example

#version 300 es precision highp float; -uniform highp sampler2D positionTex; -uniform highp sampler2D velocityTex; +uniform highp isampler2D positionTex; +uniform highp isampler2D velocityTex; uniform vec2 canvasDimensions; uniform float deltaTime; out ivec4 outColor; vec2 euclideanModulo(vec2 n, vec2 m) { return mod(mod(n, m) + m, m); } void main() { // there will be one velocity per position // so the velocity texture and position texture // are the same size. // further, we're generating new positions // so we know our destination is the same size // as our source // compute texcoord from gl_FragCoord; ivec2 texelCoord = ivec2(gl_FragCoord.xy); - vec2 position = texelFetch(positionTex, texelCoord, 0).xy; - vec2 velocity = texelFetch(velocityTex, texelCoord, 0).xy; + vec2 position = intBitsToFloat(texelFetch(positionTex, texelCoord, 0).xy); + vec2 velocity = intBitsToFloat(texelFetch(velocityTex, texelCoord, 0).xy); vec2 newPosition = euclideanModulo(position + velocity * deltaTime, canvasDimensions); - outColor = vec4(newPosition, 0, 1); + outColor = ivec4(floatBitsToInt(newPosition), 0, 1); }

I hope these examples helped you understand the key idea of GPGPU in WebGL is just the fact that WebGL reads from and writes to arrays of data, not pixels.

Shaders work similar to map functions in that the function being called

for each value doesn’t get to decide where its value will be stored.

Rather that is decided from outside the function. In WebGL’s case

that’s decided by how you setup what you’re drawing. Once you call gl.drawXXX

the shader will be called for each needed value being asked “what value should

I make this?”

And that’s really it.

Since we made some particles via GPGPU there is this wonderful video which in its second half uses compute shaders to do a “slime” simulation.

Using the techniques above here it is translated into WebGL2.